- Home

- The Clemente Family

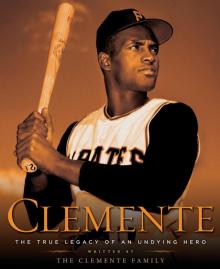

Clemente

Clemente Read online

CLEMENTE

Celebra

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com.

First published by Celebra,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First Printing, October 2013

Copyright © 21 in Right, 2013

Photos property of Clemente Photo Archive

Photo on page 140 courtesy of Neil Leifer/Getty Images

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

CELEBRA and logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA:

Clemente family

Clemente: the true legacy of an undying hero/The Clemente Family.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-1-101-61684-0

1. Clemente, Roberto, 1934–1972. 2. Clemente, Roberto, 1934–1972—Family. 3. Clemente, Roberto, 1934–1972—Death and burial. 4. Clemente family—Interviews. 5. Baseball players—Puerto Rico—Biography. 6. Humanitarians—United States—Biography. I. Title.

GV865.C45C54 2013

796.357092—dc23 2013017078

[B]

Designed by Pauline Neuwirth

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however the story, the experiences and the words are the author’s alone.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

To Vera Clemente…

who continues to represent her family and the sport of baseball

with dignity and class

CONTENTS

| INTRODUCTION |

THEIR STORY

| CHAPTER ONE |

LOVE

| CHAPTER TWO |

SACRIFICE

| CHAPTER THREE |

MEMORIES

| CHAPTER FOUR |

“A MAN OF HONOR PLAYED BASEBALL HERE”

| CHAPTER FIVE |

HOMBRE INVISIBLE

| CHAPTER SIX |

EMERGENCE

| CHAPTER SEVEN |

PREMONITIONS

|| CHAPTER EIGHT |

ETERNAL

| EPILOGUE |

21

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

| INTRODUCTION |

THEIR STORY

“If you have a chance to accomplish something that will make things better for people coming behind you, and you don’t do that, you are wasting your time on this Earth.”

—Roberto Clemente

As a young journalist, I once asked Muhammad Ali who were the athletes he admired the most. It didn’t take long for him to mention Roberto Clemente.

“I think the greatest thing you can say about a person,” Ali said, “is that they gave their life for their cause. That’s what Roberto Clemente did. He was a beautiful human being.”

Roberto Clemente spent his life helping others and died while doing so. He was dedicated to family, baseball, and aiding, in many cases, total strangers. Before the modern era of slick publicists, Twitter, and Facebook, Clemente empowered the poor and downtrodden with little acclaim. He died in a plane crash forty years ago while en route to help the Nicaraguan people who had been devastated by an earthquake. The plane was overloaded with tons of supplies.

Clemente was one of my childhood heroes. I was deeply affected by the fact that he gave his life trying to help others. There was also my admiration for what I considered his vastly underrated athletic ability, generated with nothing but spit and hard work. Clemente achieved a level of strength and speed—especially in his throwing arm—that only a handful of other players reached in the presteroid era. He was in the same talent class as contemporaries Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle.

Clemente has been called the Latino Jackie Robinson. He was the first Latin player elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, the first to win a World Series title as a starter, a World Series MVP, and an MVP award. The more appropriate Clemente comparison isn’t Robinson but Lou Gehrig. They were two baseball greats lost long before their time—Clemente in an accident and Gehrig from a deadly disease. Gehrig was the first baseball player to have the Hall of Fame’s five-year waiting period waived. Clemente was the second. Clemente died at the age of thirty-eight, and Gehrig said his iconic good-bye to baseball when he was thirty-seven.

One of Clemente’s former Pirates managers, the late Bobby Bragan, said that when he heard about Clemente’s death, he had the same pit in his stomach as when he first learned of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Clemente overcame great racism in the post-Robinson era, which remained a brutal time in American history for athletes of color, despite Robinson’s groundbreaking achievement. The bigotry of the time—early in Clemente’s career he couldn’t stay in the same hotels as some of his white teammates—prevented many fans and some of the writers who covered him from seeing the truth about Clemente, who, in addition to being an artistic baseball player, also studied ceramics, wrote poetry, and played music. He was intensely loyal. Clemente had a saying: “Never lie to me, and we’ll always be friends.”

In the early 1980s, television producer Maury Gable attempted to get a film made about Clemente’s life. Gable created a TV movie about Pittsburgh Steelers running back Rocky Bleier’s comeback from wounds he received fighting in the Vietnam War. He found Clemente’s story of athleticism, grace, and sacrifice to be equally compelling. But Gable ran into a problem. “The networks weren’t interested in a movie about a Puerto Rican ballplayer,” he said. So, even then, more than ten years after his death, many aspects of mainstream America didn’t fully comprehend Clemente’s importance in sports history.

It remains highly interesting that all these decades later, in a sports movie industry that cherishes films about the underdog—Rocky, Rudy, Miracle, and Hoosiers to name a few—no movie about another underdog in Clemente has been made.

In the Latino community, then and now, Clemente is more than cherished. He remains genuinely loved. When Ozzie Guillen was a shortstop for the Chicago White Sox, he kept an altar to Clemente in his home, complete with pictures and statuettes. Go to any ballpark in the world and the Clemente name is still admired.

The anniversary of his death, which will result in the celebration of his life, comes at an interesting time in sports history. Never before in sports has the genuineness of athletes—their performances on the field and what they do off of it—been questioned as deeply as now.

What the life of Clemente taught us was that his era, though complicated with issues of race and power, was simple in one big way: You could believe your eyes. There was no human growth hormone in Clemente’s blood. Just humanness.

Most of my life has been spent studying and writing about sports history, and to me, Clemente represents the greatest combination of athlete and humanitarian who ever lived.

The things that have been said about Clemente over the years remain remarkable. “Roberto Clemente was the best unorthodox player this game has ever seen,” said Don Baylor, who has

been a major-league player or manager since 1970, and won the 1985 Roberto Clemente Award. “The thing that made him special was the results. He said, ‘I believe we owe something to the people who watch us play.’”

“Clemente was bigger than life as far as his arm was concerned,” said Tim McCarver, who played against Clemente for more than ten years. “What made it unique with Roberto was his whirl and throw. He would actually field the ball off the carom in that short, but very difficult Forbes Field wall, catch it, pivot on the back foot, and turn and throw almost blindly at times.”

“He made the greatest throws I ever saw in my life,” former major leaguer Rusty Staub said. “He would go into that bull pen [near the right-field line in Forbes Field] where you couldn’t see home plate. One time, he went for a ball that spun into the bull pen. A guy was tagging up from third base with one out. He knew he had it made; he didn’t run hard. All of a sudden this rocket came from nowhere. It was like a strike, right across the plate. He [Clemente] couldn’t even see home plate.”

“I looked at Roberto pretty much the way I looked at my dad: as someone who was invincible, someone that would always be there,” said former Pirates teammate Al Oliver.

Clemente’s significance can still be measured: in the tiny ballparks from the United States to Puerto Rico and many other parts of Latin America; in the major-league stadiums that still feel his import; in the stadium in Puerto Rico that still bears his name; in the words of two U.S. presidents across several decades who honored him; in the award named for him and presented by baseball yearly to players who are special on the field and charitable off of it; and, perhaps most of all, how his widow, Vera, continues his legacy with honor and humility.

I spent months with the Clemente family—Vera, and three sons, Roberto Jr., Luis, and Ricky—listening to their stories about a great husband, father, and friend. Ricky, in fact, submitted to his first-ever interview. (Some family members, and close friends called Roberto by his nickname, Momen, but for the sake of clarity I have them using his formal name for this book. The nickname, says Clemente’s only surviving brother, eighty-five-year-old Justino Clemente Walker, comes from when Roberto was a child. Family members would call to Clemente and he’d always reply, “Momentito”; Momentito became Momen. Justino, meanwhile, looks like a man in his fifties, and his memory remains sharp.)

The family has continued their father’s life of selflessness, and done so in classy Clemente form. In two decades of practicing journalism, I have never met a more sincere and decent group of people. In a short period of time, I came to cherish them.

This book is their memory of a man they knew better than anyone. This is their story as told to me.

Many of the stories they tell have not been heard before. This is what makes their book unique, because it’s a view of their father directly from their eyes, minds, and hearts. Some of the photographs in this book have also never been seen before.

Other parts of the book contain interviews from friends of the Clemente family and former teammates, and previous interviews from other journalistic sources, including books, magazines, and daily newspaper articles from both the United States and Puerto Rico spanning four decades. They are all properly credited.

Not long after Clemente’s death, a nun from Pittsburgh who was a teacher at the San Antonio Catholic School in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, told her student that God had wanted Roberto Clemente’s resting place to be in the ocean so that he could spread across the universe. Vera found out about this thanks to Lourdes Berrios, her beloved neightbor’s daughter, because she was a student at the school. That is how Clemente affected people—then and now.

There is no greater example of Clemente’s generosity and dedication than the fact his life ended while he was on a mission of mercy.

“He loved the game and he was always trying to stress to his contemporaries that it was a game you have to dedicate yourself to,” Clemente’s friend Luis Mayoral once said. “…[H]e had the mind of a philosopher. He had the fire within him, a lot of pride, but it was not the kind of pride that would ever allow him to downgrade another individual. I like to think of him in terms of his hands. He had strong hands, the claws of a tiger. He had ferocity in his hands, but they were the same hands who would pat the heads of the children. He created a conscience related to the strugglers: the guy in the factory in Pittsburgh, the guy in the factory in Puerto Rico, the taxi driver, the nine-to-five guy. His sense of pride was their sense of pride. I think he would still be in the game somehow, but I see him [as] more of a sociologist, not necessarily a politician. He was trying to help people better themselves.”

In the 1994 All-Star game in Pittsburgh, a bronze statue of Clemente was revealed, created mostly thanks to funds donated by the Pittsburgh players. One of them was Orlando Merced, who grew up across the street from Clemente in Puerto Rico. He told Sports Illustrated then: “Roberto Clemente means a dream to me, and to a lot of kids and people. I never met him, but I played baseball inside his house, around the Gold Gloves, the silver bats, the trophies, the pictures. He has pushed me to be a better player and a better person. When they unveiled the statue, I was crying. It made me proud to be who I am and to be a Puerto Rican.”

“When I put on my uniform,” Clemente once said, “I feel I am the proudest man on Earth.”

“He gave the term ‘complete’ a new meaning. He made the word ‘superstar’ seem inadequate. He had about him the touch of royalty.”—Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn (1973 eulogy).

—MIKE FREEMAN

| CHAPTER ONE |

LOVE

I see him all the time. I see him mostly in his quiet moments. Sometimes he’s playing with the kids. Sometimes he’s laughing. He was a great husband to me. He was a great father. He wrote poetry. I called him Roberto.

We met in a drugstore in Carolina, Puerto Rico. I was working at a bank. One afternoon, I went out to buy something at the drugstore. When I got there, Roberto was sitting in a chair, reading the newspaper. He looked up. It was like something from a movie. I knew who he was and I was a little starstruck. He asked my name, I told him, and then I started to leave. He said, “Don’t leave.” That was how we met. He had a very kind smile.

I came from a strict family. I was shy, and when he first asked me for a date I said no. He had his niece call me at the bank, and I’m not sure why, but that made me say yes.

He came to the Banco Gubernamental de Fomento, where I used to work, to take me out to lunch. He waited outside. The employees went outside, two at a time, to see him. We went to lunch at the Caribe Hilton and I could see he was sincerely interested in me. He was dressed in a suit. He drove a white Cadillac and opened the door for me to get in. I was nervous and pressed tight against the [passenger-side] car door. He was very kind.

After that, he went home to his mother and said he’d found the girl he was going to marry. He was romantic that way. The first time he came to my home, Roberto said he was going to marry me. A few dates later, he brought pictures of houses. He also brought a diamond ring. He wanted to marry quickly, because he had to get to spring training very soon. [She laughs.]

My father was not convinced. We were married on November 14, 1964.

He planned everything fast, because he used to always say, “I’m going to die young.”

Roberto was a great baseball player, but he was a great father and husband. He also could do many other things. He could write poetry. I remember a Father’s Day game in Pittsburgh, and he was in full uniform. He was writing on the back of a piece of paper. It was poem. It was called “¿Quién Soy?”—“Who Am I?”

Who Am I?

I am a small point in the eye of the full moon.

I only need one ray of the sun to warm my face.

I only need one breeze from the

Alisios to refresh my soul.

What else can I ask if I know that my

sons really love me?

I loved him so much.

There was a

time in November, not long before the crash, when Roberto woke up in the middle of the night. I remember him saying, “I just had a very strange dream. I was sitting in the clouds, watching my own funeral.”

The last time I saw him, he was boarding the plane. He stood in the doorway of the plane and looked back to me. He had a very sad look. I’ll never forget that look.

VERA CLEMENTE: He loved baseball since he was a child. I think that’s all he ever wanted to do. He wanted to be a great baseball player.

LUIS CLEMENTE (son): My dad was a happy guy, but he was very happy when he was with his family, and happy when he was playing baseball.

ROBERTO CLEMENTE JR. (son): He was a kind man and a great dad, so it was always strange to hear and later read about how ruthless he was as a baseball player.

RICKY CLEMENTE (son): Through his actions, Dad taught us to treat people the way you want to be treated. He taught us to be kind to everyone and not care about a person’s color. That message stuck with all of us.

ROBERTO CLEMENTE, 1961: I am between the worlds. So anything I do will reflect on me because I am black and…will reflect on me because I am Puerto Rican. To me, I always respect everybody. And thanks to God, when I grow up, I was raised…my mother and father never told me to hate anyone, or they never told me to dislike anyone because of racial color. We never talked about that.

VERA: Right before the [plane] accident, he was supposed to give a baseball clinic to kids in Puerto Rico. He did that all the time. His sons saw things like that and tried to be like their dad in that way. [The field where Clemente gave many of those clinics still exists in Puerto Rico.]

JUSTINO CLEMENTE WALKER (Clemente’s eighty-five-year-old brother): Roberto rarely took time for himself. His time was for others, his family, strangers. Only time he did something for himself was after the season. He’d go to a farm he owned near the [El Yunque] rain forest. He’d just relax. If the Pirates weren’t in the World Series, he’d relax on that farm and watch the World Series on television. He once spent the day with Martin Luther King in his other farm in Martin González in Carolina. They talked about everything. Roberto admired how [King] gave poor people a voice.

Clemente

Clemente